Introduction

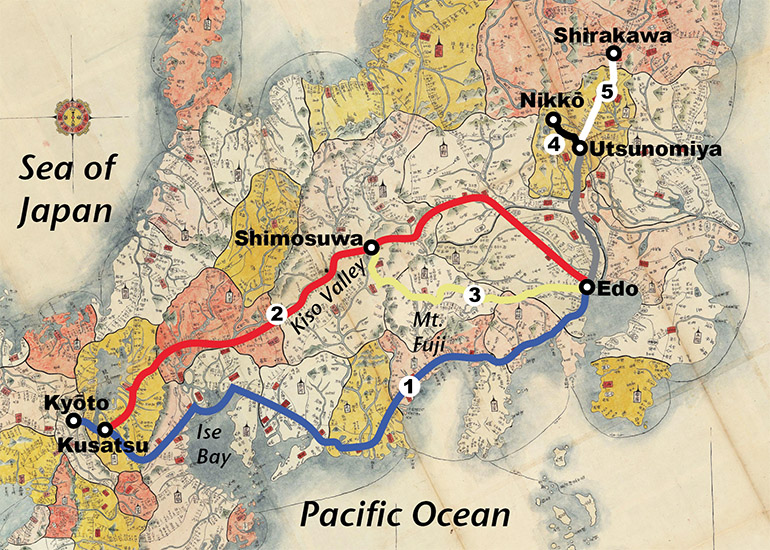

During the Edo Period (1603–1868), the Tokugawa shogunate established Five Main Roads (五街道, Gokaidō) to facilitate travel to and from Edo Castle, the shōgun’s headquarters in Edo. Three roads went west from Edo to Kyōto, where the emperor, who appointed the shōgun, resided in the Imperial Palace. Two roads went north from Edo, one to Nikkō and one to Shirakawa. The five roads had government-designated stations where official travelers could find lodging and transport services.

The Five Main Roads were the following:

- Tōkaidō (東海道, Eastern Sea Road): The 307-mile-long Tōkaidō went from Edo to Kyōto along the southern coast of Honshū island. (For woodblock prints and photos of the 53 stations along this road, see “Scenes along the Tōkaidō.”)

- Nakasendō (中山道, Middle Mountain Road) also connected Edo and Kyōto, but went through the central mountains of Honshū. The 332-miles road was also known as the Kisokaidō (Kiso Road) after its most famous section, an ancient trade road through the Kiso Valley. The Nakasendō joined the Tōkaidō at Kusatsu station near Kyōto and the two roads continued on the same route from there via Ōtsu to Kyōto. (For woodblock prints and photos of the 69 stations along this road, see “Scenes along the Kisokaidō.”)

- Kōshū-kaidō (甲州街道 Kōshū Main Road) went between Edo and Shimosuwa, Nakasendō station 29, in Shinano Province. The 134-mile Kōshū Road went east from Edo through Kai Province. (Kōshū was another name for Kai Province, today Yamanashi Prefecture. See “Touring Yamanashi.”)

- Nikkō-kaidō (日光街道, Nikkō Main Road) connected Edo to Nikkō, where the deified spirit of Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), the founder of the Edo shogunate, was enshrined at Tōshōgū (“Palace of the Eastern Light”) in 1617. The road went 65 miles north of Edo to Utsunomiya (station 17), then 25 miles northwest to Nikkō. (For photos along the Nikkō Road, see the notes to “Bashō’s Narrow Roads of the Deep North (2): Nasu to Shirakawa.””)

- Ōshū-kaidō (奥州街道, Ōshū Main Road). From Utsunomiya, station 17 on the Nikkō-kaidō, the Ōshū-kaidō branched to the northeast and went 62 miles to Shirakawa, a castle town in Mutsu Province. (Ōshū was another name for Mutsu; for photos along the Ōshū Road, see “Bashō’s Narrow Roads of the Deep North (2): Nasu to Shirakawa.”)

1. Travelers

Initially, the main purpose of the three government roads between Edo and Kyōto was for travel by shogunate officials to and from the Imperial court in Kyōto. Messengers carrying letters and documents between Edo and the court also used the roads.

In 1632, the shogunate began requiring lords it assigned to rice-producing domains to live alternate years in Edo and perform services like fire-watches and guard duty at the gates of Edo Castle. The shogunate specified the months of attendance for each lord and the roads on which they were to travel to Edo Castle. As the lords and their retinues approached Edo, they traveled on the Five Main Roads.

A woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) depicts the procession of a lord (大名, daimyō) on the Nakasendō leaving Kanō Castle (in present-day Gifu City).

By 1853, there were 265 domain lords, who (with some exemptions for lords assigned other duties) made alternate-year journeys to and from Edo. The processions of these lords were a common sight on the Gokaidō.

The shogunate specified the number of retainers and servants that lords could bring to Edo, based on the rice-production of their domains (藩, han); but since the lords considered the size of their entourages expressions of their status and prestige, early in the Edo Period, they exceeded the limits set. Processions for the larger domains included from 1,000–4,000 attendants; the lords of smaller domains brought less than a hundred. Eventually, the retinues averaged about 150–300 members.

The lords were carried in enclosed palanquins (乗物, norimono) by two or more porters; the rest of their retinues generally walked; a few rode horses. Luggage was carried by porters and packhorses led by drivers provides for them free of charge.

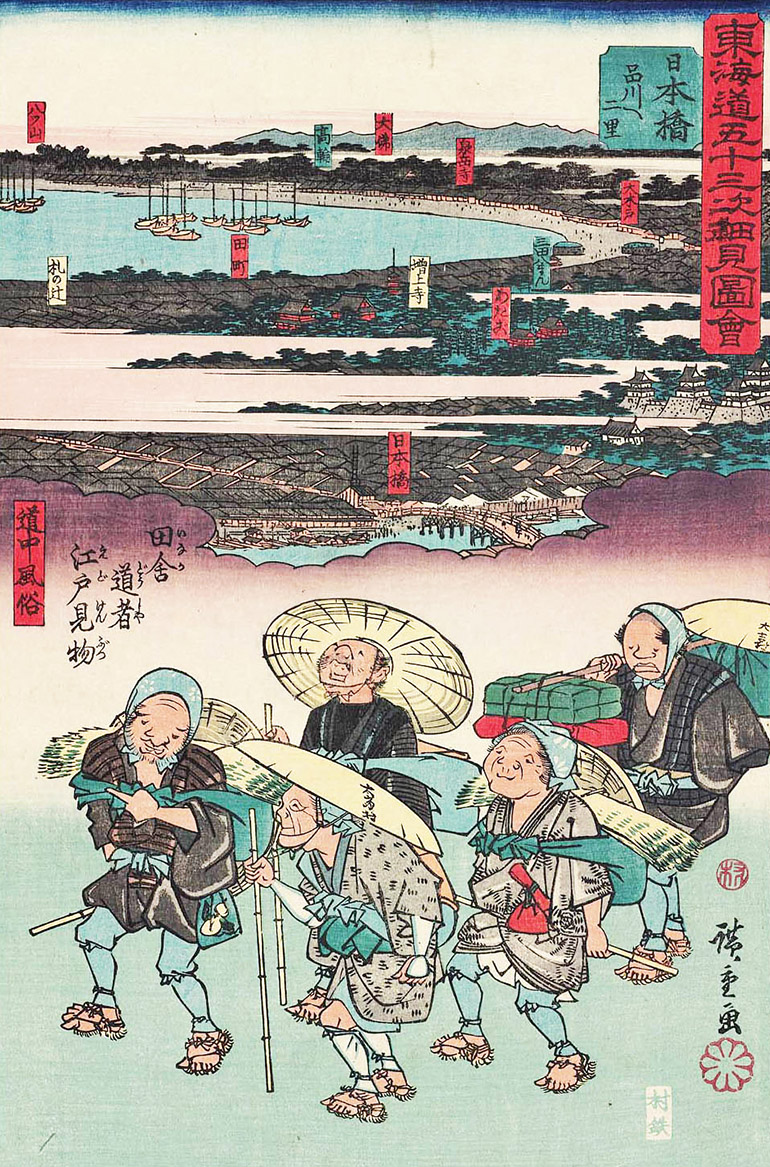

After centuries of internecine warfare among rival lords, the shogunate unified the nation and kept it at peace for over two and half centuries. Cities and towns grew, local economies expanded, people prospered, and travel became a popular pastime. While travel by commoners was restricted at first, pilgrimages to temples and shrines were allowed. Another Hiroshige print (below) depicts a scene near Ōdai station on the Nakasendō with pilgrims crossing an autumn field.

Eventually, more and more common people took to the road, purportedly on pilgrimages, but also for leisure and adventure. On their journeys, they could use the Five Main Roads, but had to show deference to shogunate officials and lords, who had the right of way as well as free inns and transport services.

Commoners who could afford it could travel in enclosed palanquins (乗り物, norimono) or in less comfortable open palanquins (駕籠, kago), which might be as basic as a basket seat suspended from a carrying pole. Commoners who had the money could also rent horses and pay to have their luggage carried by porters or packhorses. The less wealthy walked and carried their own belongings.

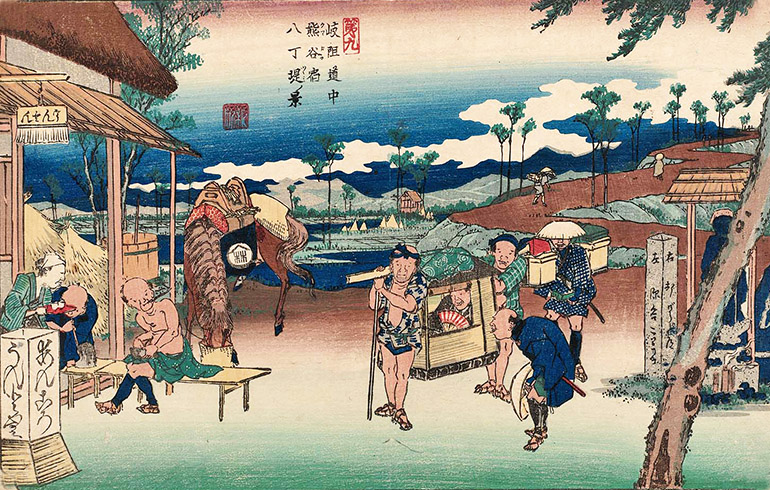

In the print below, a wealthy traveler in an enclosed palanquin stops to talk with a traveler on foot outside a teashop in Kumagaya (Nakasendō station 8); a porter carrying luggage follows. A women serves tea to a traveler and a packhorse driver who are seated smoking pipes on benches at the teashop. The packhorse feeds from a bucket behind its driver.

2. Government Roads

The five government roads were maintained by conscripted laborers (able-bodied men between 15 and 60 years of age) whom the shogunate required the domains along the roads to provide, from towns designated as stations (see below) and their surrounding villages.

Compacted gravel and sand surfaces kept the road relatively hard and dry; drainage ditches along the roads reduced puddles and erosion. Stone pavement (石畳, ishi-tatami) was laid in some places, particularly on slopes, to improve footing and make the roads easier to ascend and descend when wet with rain.

The roads were on average between 18 and 24 feet wide, as wide as 48 feet and as narrow as 9 feet in places. Rows of trees (並木, namiki), mainly cedars and pines, were planted along stretches of the road to provide shade and shelter for travelers, to serve as wind breaks, and to prevent erosion.

The roads crossed rivers, some of which were bridged.

Ferries carried travelers across rivers without bridges.

Shallow rivers were forded. Lords and ladies and the wealthy were carried in palanquins on platforms hoisted on the backs of river porters; others travelers sat on platforms or were piggy-backed. When the rivers were flooded, travelers waited at stations on either bank, sometimes for days or weeks, until the waters subsided.

To bypass wide rivers flowing into Ise Bay from the north, the Tōkaidō included a seventeen-mile sea crossing of the bay, between Miya and Kuwana (Tokaidō stations 41 and 42) .

3. Stations

Since the Heian Period (794–1185), the central government had designated towns to serve as stations (宿駅, shuku-eki) on important roads, based on a Chinese model. At these stations, official travelers could find transport services—porters and packhorses to carry loads as far as the next station. In China, stations were located about 73 miles (30 li) apart; in Japan, where the routes were shorter, but more mountainous, stations were located on average about 12 miles apart. While providing relay horses was the main function of these stations, the station building for transport services also allowed travelers to lodge overnight.

After the Heian Period, with the weakening of the central government, the national highway system broke down, and in the following centuries, rival warlords carved out separate domains and battled each other for supremacy.

During the Edo Period, after the nation was unified under the Tokugawa shogunate, the practice of designating towns with travel services was revived to facilitate official travel on government roads. The towns were called shuku-ba-machi (宿場町) or shuku (宿) for short, literally “lodgings,” but variously translated “relay stations,” “post stations,” “post towns,” or simply “stations.” Stations were required to provide transport services (packhorses with drivers and porters) and lodgings free for travelers on shogunate business; other travelers could pay for the services. In exchange for the travel services, the towns were granted tax-free land and stipends for officials to oversee the services.

There were 53 stations on the Tōkaidō, and 69 stations on the Nakasendō. (In the titles of print series illustrating scenes on the road such as Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō and Sixty-three Stations of the Nakasendō, the word translated as “stations” is not “shuku [宿]” but “tsugi [次],” which is translated as both “stations” or “stages.”

4. Inns

Stations on the Gokaidō were required to have at least one honjin (本陣), a lodging where high-ranking government officials and lords stayed for free; and waki-honjin (脇本陣, “supporting honjin”) to house the entourages that accompanied officials and lords on their travels. A couple of stations on the Nakasendō lacked honjin, but could house guests at a castle (Takasaki, station 13) or at temples (Iwamurata, station 22).

The term honjin (“base camp”) originally referred to the battlefield headquarters of a general; once designating the area where a general sat in a temporary enclosure, honjin evolved into buildings constructed at the site of a siege, protected by walls and moats. During the Tokugawa peace, the term was used to refer to the lodgings for lords who were on the road, traveling away from home. The honjin was often the residence of the village headman or its wealthiest person; the owner was allowed to construct gates at the entrances to his residence.

As travel by commoners increased during the Edo Period, so did paid lodgings to accommodate them. Such inns for commoners were called hatago (旅籠, literally, “travel coop,” suggesting crowded conditions and small rooms). In 1843, a small station like Hara (Tōkaidō station 13) had 16 such inns while a large station like Miya (Tōkaidō station 41) had 248.

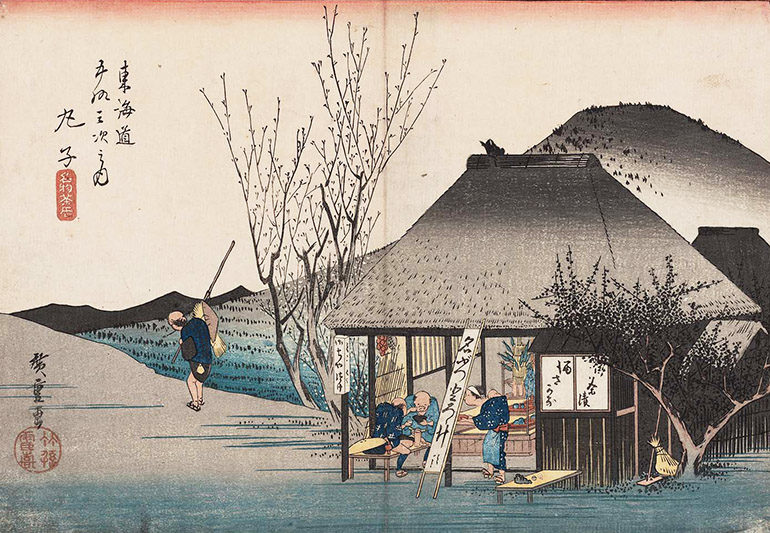

The stations also had shops that sold food, tea, and travel supplies (sandals, raincoats, and straw or sedge hats), as well as local specialities products to consume on the road or to carry home as gifts.

The government road was the main thoroughfare in the towns (and in small villages, the only road);inns and shops were built along each side of the road.

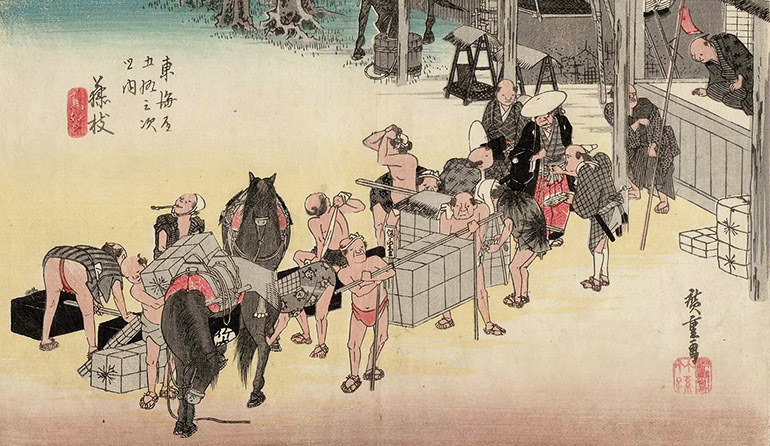

5. Transport Services

Transport services at the stations were housed in the warehouses (問屋, ton-ya or toi-ya), where baggage could be stored and porters and pack horses were available to transport it to the next station. Like the workers who maintained the roads, the transport workers were conscripted. The services were free for travelers on shogunate business; at a fixed rate for other government officials and lords; and at negotiable rates for commoners.

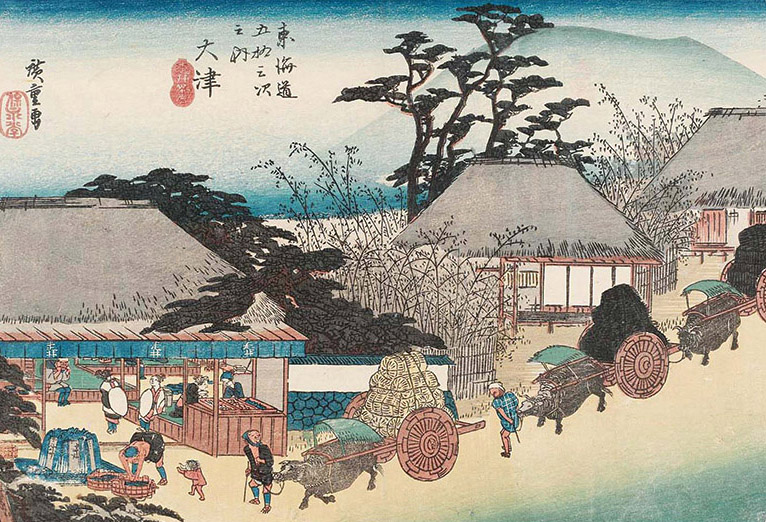

Two-wheeled carts, ox-drawn or hand-drawn, were used to move heavy loads in cities, but were prohibited in some towns and cities or along stretches of the road to prevent rutting. They were impractical in mountainous areas. Their use was also generally opposed by the packhorse drivers, porters, and ferry men who competed with cart owners for cargo. Overall, carts are depicted in Edo Period woodblock road prints in scenes of towns and cities where carts were allowed, as in Edo and Ōtsu, a Lake Biwa port that served nearby Kyōto.

Large shipments of cargo were transported mainly by sea, between seaports on the coast; or inland, by river in boats or in the case of logs, bundled together into rafts.

6. Station Entrances

Stations extended along both sides of the government roads, with an entrance (見附, mitsuke, approach) at both ends marked by sign posts and sometimes a stone wall. The entrances on the roads betwen Edo and Kyōto were identified as “Edo-side” (east side) or “Kyōto-side” (west side).

Stone lanterns known as joyato (常夜灯, “all night lights”) were placed at both entrances of the stations to light the way for late-arriving travelers. The lanterns, erected by the towns themselves rather than under shogunate order, were lit at nightfall and burned until first light.

Government bulletin boards (高札場, kosatsuba) posted important information and notices—laws and regulations, a moral code, rates for porters and pack horses, etc.

The road approaching a station sometimes had a zigzag pattern, as in the print below of the approach to Nakatsugawa (Nakasendō station 45).

The zigzag pattern was a traditional Chinese design based on the belief that evil spirits or angry ghosts could only travel in straight lines and were thus prevented from entering a village by crooked roads. The practical purpose of the zigzag may have been to give villagers time to identify who was coming and to prepare themselves, whether for friends or foes. The Tokugawa shogunate required important stations to build one or more 90 degree turns (masugata, 升形, box-figure) at the approach to entrances, a pattern used at the approach to castles to prevent direct attacks.

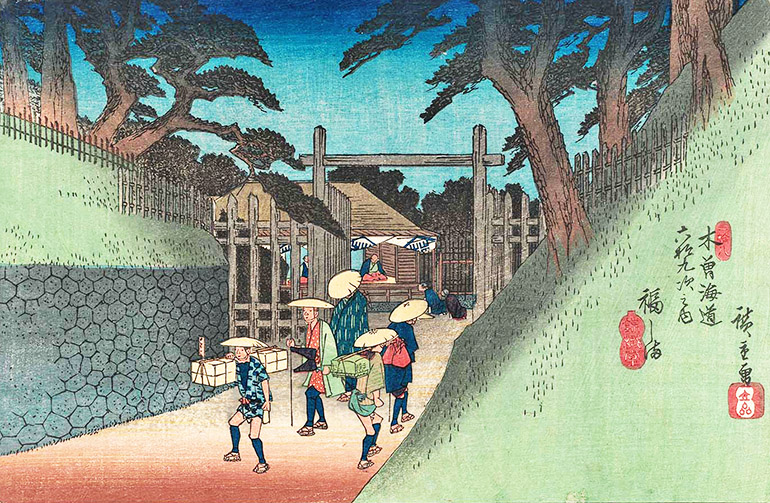

7. Barrier Checkpoints

Travelers and cargo were checked and inspected at barrier gates (関, seki) established at strategic locations on the roads. On the Tōkaidō, the major checkpoints were located at Hakone and Arai (stations 10 and 31); on the Nakasendō they were located at Usui near Sakamoto (station 17) and at Kiso Fukushima (station 37) .

At these checkpoints, shogunate officials watched for suspicious movement of people and goods; specifically, tbey checked baggage to prohibit guns from being transported to Edo without permission. In 1634, the shogunate decreed that the wives of all the domain lords, with their children, should remain in Edo as hostages while their husbands returned to their home domains. Checkpoint officials were charged with checking for wives and children leaving Edo without shogunate permission.

8. Distance-Marking Mounds

The starting point of the government roads was a zero-marker at Nihonbashi (Japan Bridge) in central Edo. From there, mounds were placed on both sides of the roads at one li intervals to the destinations. The mounds were called ichi-ri-zuka (一里塚, one-li mounds; a li was equal to 2.44 miles.) The mounds were generally 9 feet high and 15 feet in diameter and planted with hackberry trees.

The practice of marking distances with ichirizuka was established by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598), a lord who ruled Japan as regent to the Emperor before the Tokugawa shogunate was established.

For woodblock prints and photos of the Tōkaidō and Nakasendō (aka Kisokaidō), see the following pages:

Scenes along the Tōkaidō

- Introduction; Eastern Terminal in Edo and Stations 1–4 in Musashi Province

- Stations 5–11 in Sagami and Izu Provinces

- Stations 12–23 in Suruga Province

- Stations 24–32 in Tōtōmi Province

- Stations 33–41 in Mikawa and Owari Provinces

- Stations 42–53 in Ise and Ōmi Provinces; Western Terminal in Kyōto, Yamashiro Province

- Google Map of the Old Tōkaidō, with historic sites marked.

Scenes Along the Kisokaidō

- Introduction; Eastern Terminal in Edo and Stations 1–10 in Musashi Province

- Stations 11–17 in Kōzuke Province

- Stations 18–29 in Eastern Shinano Province

- Stations 30–43 in Western Shinano Province

- Stations 44–59 in Mino Province

- Stations 60–69 in Ōmi Province

- Google Map of the Old Nakasendō (Kisokaidō, with historic sites marked.

Related Websites

- Hiroshige’s Famous Places in the 60+ Provinces (1853–1856; prints and photos of a famous place in each of the 60+ Edo Period provinces of Japan)

- Bashō’s Narrow Roads to the Deep North (1689)

- Bashō’s “Sarashina Travel Journal” (1688)

Pacific Journeys: Home and Away

FAMILY AND HOME ||| TRAVELS IN THE PACIFIC ||| ROAD TRIPS IN JAPAN ||| EDO ROADS